Professor Mikhail Tiunov, PhD in Biology, lead researcher at the Theriology Laboratory of the Federal Scientific Centre for Biodiversity, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, together with an international team from China, Russia, the US, Malaysia, and Denmark, took part in a study of the tiger’s evolution based on the analysis of ancient genomes, according to the Amur Tiger Centre.

Scientists selected more than 60 samples, ranging in age from 100 to 10,000 years, found in the Middle and Far East and Central and South Asia. The results of the work were published in the Nature Ecology & Evolution journal and are also available on the website of the Federal Scientific Centre for Biodiversity of Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

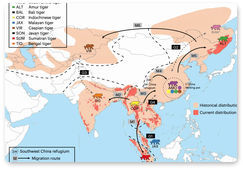

According to the results of the research, some specifics of the mitochondrial DNA show that ancient tigers had higher genetic diversity than today's tigers. In the geological past, the tiger's range was reduced to the territory in southwest China due to landscape and climatic changes.

As the environment suitable for tiger habitat was restoring, various lineages of southern Chinese tigers inbred in East China, thus facilitating the evolution of the northern subspecies. The spread of the tiger into Northeast Asia and then west into Central Asia linked the northern subspecies (Amur and Caspian) with the southern mainland subspecies (Bengal and Indochinese).

The 10,600-year-old specimen found in the Russian Far East bore genetic similarities not only to the Amur tiger living in the area today, but also to other tiger populations further south. Together they form a sister group to the South China tiger group.

Scientists have proven that the Caspian tiger descended from an ancestral population in Northeast Asia, receiving fresh genes from southern Bengal tigers. The status of an independent subspecies of the South China tiger has been confirmed.

Research has also confirmed that there were nine living subspecies of tigers, three of which went extinct in the 20th century because of human activity. Scientists say a detailed understanding of the tiger’s genomic diversity and evolution is critical to conservation and recovery planning for the species and will influence tiger management strategies both in the wild and in captivity.

“This research makes it possible for us to understand what happened and what can happen to certain tiger populations while their habitat’s conditions are changing due to changes in the environment. It also provides for a way of addressing the task of defining tiger subspecies: they are geographical forms associated only with living conditions, or forms of occurrence determined by what happened to them in the distant past. The work also makes it possible for us to understand what we can do in terms of relocation, crossing of different subspecies, and what specifically needs to be done for their conservation. Right now, our research is aimed at locating and studying even older tiger fossils in Primorye,” said Professor Mikhail Tiunov, PhD in Biology, lead researcher at the Theriology Laboratory of the Federal Scientific Centre for Biodiversity, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

ABOUT THE PROGRAMME

ABOUT THE PROGRAMME

AMUR TIGER: LIFE, BEHAVIOUR AND MORE

AMUR TIGER: LIFE, BEHAVIOUR AND MORE

AMUR TIGER RESEARCH: A HISTORY

AMUR TIGER RESEARCH: A HISTORY

VLADIMIR PUTIN'S VISIT

VLADIMIR PUTIN'S VISIT

NEWS

NEWS

MULTIMEDIA

MULTIMEDIA