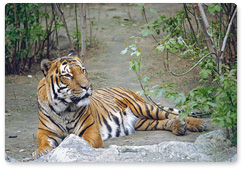

Roskosh the tigress, a notorious troublemaker, was caught in early June 2011 by specialists from the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution and the Tiger Special Inspectorate on instructions from the Federal Service for Supervision of Natural Resources (Rosprirodnadzor). She has now been transferred from the Utyos rehabilitation centre in the Khabarovsk Territory to the Yudin Zoological Centre in Primorye, where she will be cared for and, in future, involved in breeding programmes. The goal is to release any offspring she may go on to have into the wild.

In late May 2011 there were several instances of the tigress attacking dogs in the Khabarovsk Territory, and she showed no fear of humans. She was caught by specialists on June 5.

The animal was named Roskosh after the village in which her fatal attacks on several dogs took place. On closer inspection, Roskosh proved to be a young and outwardly completely healthy female: she weighed about 110 kg and had all her teeth intact. While conducting routine tests for infectious diseases and deciding her fate, the predator was kept at the Utyos animal rehabilitation centre.

Under the program for the study of the Amur tiger in Russia’s Far East, members of the Russian Academy of Sciences’ permanent expedition, and specialists from the parasitology department at the Skryabin Moscow State Academy of Veterinary Medicine and Biotechnology, analysed serum and blood smears from the tigress.

The tests showed a seronegative reaction to the following antigens: canine distemper virus, feline distemper, herpes simplex type I and II, feline immunodeficiency, feline coronaviral enteritis, feline leukemia, mycoplasma and chlamydia. The blood smears also revealed no piroplasmosis pathogens.

At the time of capture, the tigress’s blood serum contained antibodies to toxoplasmosis. This means the tigress had either come into contact with an agent of that disease or is herself a carrier. But even if she is a toxoplasmosis carrier, her risk of death is minimal: specialists from the permanent expedition say that one-third of adult wild tigers are seropositive for toxoplasmosis, another quarter yield unclear results and about 40% are seronegative.

Test results gave this female tiger a clean bill of health. But due to her behaviour (repeated appearances in human population centres and her predilection for hunting domesticated dogs), the Institute recommended that the animal not be released back into the wild, instead passing her into the care of renowned specialist Viktor Yudin. He will oversee her care and future involvement in breeding programmes.

Any offspring she may go on to have could be housed at a tiger rehabilitation centre that is currently being built in the Primorye Territory. This facility is a collaborative project between the Severtsov Institute and the Tiger Special Inspectorate under the Amur Tiger Programme for Russia’s Far East, and is sponsored by the Russian Geographical Society. Tigers housed at that facility would later be released into the wild as part of tiger re-introduction programmes.

On August 4, permanent expedition specialists took the tigress to her new residence.

ABOUT THE PROGRAMME

ABOUT THE PROGRAMME

AMUR TIGER: LIFE, BEHAVIOUR AND MORE

AMUR TIGER: LIFE, BEHAVIOUR AND MORE

AMUR TIGER RESEARCH: A HISTORY

AMUR TIGER RESEARCH: A HISTORY

VLADIMIR PUTIN'S VISIT

VLADIMIR PUTIN'S VISIT

NEWS

NEWS

MULTIMEDIA

MULTIMEDIA