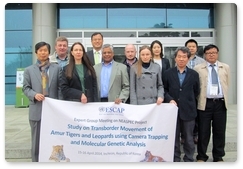

Last week, the city of Incheon in South Korea hosted an expert meeting on studying and preserving the Amur tiger and Far Eastern leopard populations. This meeting was held as part of an international research project on cross border movements of rare cat species that involves the use of trail cameras and molecular and genetic analysis methods. Land of the Leopard National Park was represented at the meeting by its research fellow Dina Matyukhina.

According to Ms Matyukhina, while international meetings on such issues are no longer a rarity, the Incheon meeting was special in a number of ways.

First, the meeting was held in an unusual location. In fact, both leopards and tigers were wiped out in South Korean forests decades ago and can no longer be found there.

Second, the meeting was special in that it yielded concrete results. For the first time ever, scientists from three countries, Russia, China and South Korea, agreed on a joint research project to study and protect wild cat species, which will consist of running molecular and genetic tests on animal faeces. The necessary biomaterial will be collected in Russia and China, while scientists from all three countries will participate in analysing the predators’ DNA.

“Apart from identifying animals and their gender, DNA tests are expected to reveal the degree of relation between animals, which is highly important for any research on animal populations,” Ms Matyukhina pointed out.

While in Incheon, she met with a group of researchers from Seoul National University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. Along with Professor Hang Lee, Chair of the Korean Tiger and Leopard Conservation Fund, they returned from a four-week visit to Land of the Leopard Park about a month ago, where they studied Russian experience in conducting research on rare cat species.

This initiative was by far not the only visit. In fact, Professor Lee has visited the national park on a number of occasions, including during the celebrations of its first anniversary in 2013. Korean researchers take special interest in the history of the Korean peninsula and its extinct species, which served as an impetus for initiating efforts to restore the population of wild cat species. Although concrete plans have yet to be devised to this effect, Korean experts are taking advantage of every opportunity to study and protect the Far Eastern leopard and Amur tiger in Russia and China.

The Korean Tiger and Leopard Conservation Fund also focuses on raising public awareness on leopards and tigers in South Korea. For instance, during her visit to Incheon, Ms Matyukhina attended an award ceremony for a children’s tiger and leopard drawing contest and awarded winners with prizes on behalf of Russian scientists.

“During my visit to Korea, I also visited forests which could be suitable for reintroduction. I did not have an opportunity to inspect the whole territory. Anyway, the main issue of this territory is its small size – just 18,000 hectares – which is not enough for sustaining a population,” Ms Matyukhina said.

Ms Matyukhina also called on her Korean colleagues to determine whether these territories are suitable for Far Eastern leopard, and to expand them. However, the possibility of expansion is contingent upon whether South Korean and North Korean leaders will be able to reach common ground, since wild forests are mostly located on the border between the two countries. The future of rare animal species is yet again directly dependent on politics.

ABOUT THE PROGRAMME

ABOUT THE PROGRAMME

FAR EASTERN LEOPARD RESEARCH: A HISTORY

FAR EASTERN LEOPARD RESEARCH: A HISTORY

FAR EASTERN LEOPARD: LIFE, BEHAVIOUR AND MORE

FAR EASTERN LEOPARD: LIFE, BEHAVIOUR AND MORE

SERGEY IVANOV'S VISIT

SERGEY IVANOV'S VISIT

NEWS

NEWS

MULTIMEDIA

MULTIMEDIA